Builder of Great Chalfield - Page 4.

Tropenell's character

There are questions that have been asked about Tropenell’s character. Was he always honest? Was he unusually rapacious? He certainly has been described as fiercely acquisitive. But it is hard to say at this distance in time whether he was worse than many others. As to his honesty there are certainly questions to be asked of his behaviour in two of the recorded cases in which he was involved. For example we have a record of it having been alleged that he bribed a jury on behalf of his patron the third Lord Hungerford.

He was also alleged to have behaved improperly in 1466 in a case with his stepson Richard Erley, who was fighting for property he believed to belong to his family. Tropenell presented a ‘bill’ to the jury when he was claiming a substantial number of properties and land described as the manor of Stitchcombe with holdings in Marlborough and Burbage. In this bill Tropenell set out exactly what the jurors should say in their verdict. They found in his favour but later swore that their verdict had not been influenced by his improper instruction to them. His opponent Richard Seymour appealed to the chancellor, Archbishop Neville, and in his appeal claimed “the jury had been partially arrayed, by steryng and naming of Tropenell and were of his affinity, that Tropenell had paid grete rewardes of money not only to the jury but to the sheriff and had manipulated the proceedings so that the defendants had not been informed of the content of the writ until the morning of the assize and the jury had been fed misinformation which they used in their verdict”. Tropenell denied all the charges, perhaps needless to say. The case finally went to the King’s Bench four years later. We do not know the final outcome, other than the admission by the jury that Tropenell had tried to guide their verdict illegally. However we know Erley relinquished to Seymour a meadow in Stichcombe and it seems likely that he had to give up his claim to the rest of the estate. Tropenell did not win them all! That he was engaged in this case at the same time as his settling of his claim to Great Chalfield and beginning the building of his manor there proves his energy, if nothing else.

He was also alleged to have behaved improperly in 1466 in a case with his stepson Richard Erley, who was fighting for property he believed to belong to his family. Tropenell presented a ‘bill’ to the jury when he was claiming a substantial number of properties and land described as the manor of Stitchcombe with holdings in Marlborough and Burbage. In this bill Tropenell set out exactly what the jurors should say in their verdict. They found in his favour but later swore that their verdict had not been influenced by his improper instruction to them. His opponent Richard Seymour appealed to the chancellor, Archbishop Neville, and in his appeal claimed “the jury had been partially arrayed, by steryng and naming of Tropenell and were of his affinity, that Tropenell had paid grete rewardes of money not only to the jury but to the sheriff and had manipulated the proceedings so that the defendants had not been informed of the content of the writ until the morning of the assize and the jury had been fed misinformation which they used in their verdict”. Tropenell denied all the charges, perhaps needless to say. The case finally went to the King’s Bench four years later. We do not know the final outcome, other than the admission by the jury that Tropenell had tried to guide their verdict illegally. However we know Erley relinquished to Seymour a meadow in Stichcombe and it seems likely that he had to give up his claim to the rest of the estate. Tropenell did not win them all! That he was engaged in this case at the same time as his settling of his claim to Great Chalfield and beginning the building of his manor there proves his energy, if nothing else.

The case of Hindon Manor which he bought earlier throws more light on how these battles of Tropenell’s for property sometimes went. He won this time, also after a long and bitter dispute, pursued by him right up to a petition to Edward Earl of March in 1460, a few months before he took the throne. Tropenell’s opponent on this occasion was Richard Page of Warminster, whose tactics throughout showed that the only trick Page did not use in the armoury developed in our time by the Mafia in Sicily and New York was the use of firearms. All the detail is in the cartulary. We must assume the official documents quoted there, some of them royal, were copied accurately.

The poor innocent who originally owned Hindon was one Robert Hurdell. He stated in court under oath that he had been tricked by Page on the promise of arranging a dowry into a meeting in the local vicarage at which Page was well supported by friends and advisors. At this meeting Page attempted to force him into selling him the manor. He produced a document of sale pretending the ink on it was just sanded when it was an old one and misled him about its terms. Hurdell perhaps could not read, or, if he could, not fast and not things in legal language. Tropenell rightly claimed that Hurdell had sold him the manor which included 19 dwellings, a bull and 700 sheep for £40, a fair sum, to take possession on Hurdell’s death. Page was willing to swear to the contrary. All witnesses, except two of Page’s ‘friends’, including Hurdell’s wife, swore that the only claim Page had on it was for the duration of Hurdell’s life, as a tenant. Page lost, was fined and threatened with prison if he did not pay. He refused to leave the manor or go to prison.

Tropenell then appealed to the Earl of March shortly after the Yorkists had won the battle of Northampton and taken control of the government. He was involved because a Welshman, Richard Gwyneth, claiming to be the Earl’s servant, had arrived at the manor while Edward was abroad, claiming that Edward had ruled in Page’s favour. Perhaps this shady character had been chosen by Page because he was not local or had a reputation as good confidence trickster. He was heard of no more. This appeal to the leader of the Yorkist side in the civil war is significant. Page saw there was a chance he could win his case even with false evidence with Yorkist support against a well known Lancastrian. ‘Silent leges inter arma’, the law is silent in war, as Cicero famously said. But in this case he was wrong. Tropenell’s two liveries meant that he too could expect favour from Edward and got it. The Earl stated he had never heard of Richard Gwyneth and after he became king he confirmed the judgement of the courts, awarding the manor to Tropenell. All of this took at least 7 years before the settlement in 1460 (Cart ii 32-82).

The reason for dealing with this at length is to show that these were ruthless times when you needed to know how to watch your back and public law enforcement was still in its infancy. Another reason is to point out that it was early in this case, when Richard Page was attempting to use all means fair and foul to persuade Hurdell to let him have the manor, that he said of Thomas Tropenell that he was ‘a perillous covetous man’’. This phrase is often quoted. It has the virtue of being memorable and doubtless had an element of truth. Enemies often see each other clearly. However this was at least a case of the pot calling the kettle black. Page was ruthlessly running someone down to win his point, with more than a touch of envy of his rival’s success in business thrown in. Tropenell comes out of the official record of this case as persistent and energetic in defending his rights, but not covetous. Nor on this occasion was there any evidence of his being dishonest. It is interesting that we owe the phrase to Tropenell’s own cartulary (ii 39). One assumes he did not think anyone would take it too seriously from the mouth of Richard Page on the hunt for a property that he lost.

However the best evidence of character with Thomas Tropenell is the way many people entrusted him with their affairs over a long period of time. Perhaps most tellingly Lady Margaret Hungerford made him one of her executors on the death of her grandson in 1469, and trusted him with her affairs to the end of her life. His last recorded service to her was to hold court for her in Penhale to settle her Cornish property in 1476, when he was about 70. She died the year after, sadly still heavily in debt from paying the French ransom for her son 20 years before. In her will she explained to her heirs that this was the reason she could not leave them ‘as much as I might and would have done, if fortune had not been so sore against me’, which makes it clear that Tropenell’s loyal service to her over many years had no mercenary motive.

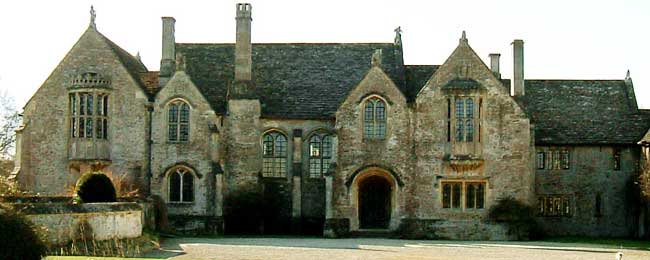

There is also what we can learn from his great manor house. The quality of its building cannot fail to impress still. The Oriel windows on the north side and the great hall with its fine ceiling that still stands with its original fireplace are exceptional. He clearly used the best local craftsmen. Other structures of this period in the area are also fine, including the Oriel windows in the Old Deanery in Wells, the Church Hall in Church St., Bradford on Avon, which has another fine original ceiling and South Wraxall Manor, three miles away. These could have provided inspiration and also are all evidence of the prosperity of the area. But there is nothing to touch his manor at Great Chalfield.

The north facade today is not greatly changed from Tropenell's day

In these and in other ways he was announcing that he was confident of his being in the ranks of the gentry. It was a case of the right man, in the right place and, most fortunately, his great project came at the right time in the history of vernacular domestic architecture.

Tropenell's family motto was painted on the original roof timbers of the Great Hall and is still visible there today.

'Le jong tyra belement' (The yoke pulls well'). His badge - a double yoke.

His inspired design is full of humorous touches too, including the monkey on the roof of the priest’s apartment, and that extraordinary painting in the dining room. It is surely a caricature he allowed to stand as a good joke, if it was put there in his lifetime. He must have known it was a caricature of a man of parts, confident of his record and lord of all he surveyed. That is how he looks still. It is a great sadness that the paintings commissioned by Tropenell on the walls of his chapel in All Saints’ Parish Church, Great Chalfield have been almost completely destroyed.